SPANISH FLU

The Spanish flu was an unusually deadly influenza pandemic. Lasting from January 1918 to December 1920, it infected 500 million people—about a quarter of the world's population at the time.It was the most severe pandemic in recent history. It was caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin. Although there is not universal consensus regarding where the virus originated, it spread worldwide during 1918-1919. In the United States, it was first identified in military personnel in spring 1918. It is estimated that about 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population became infected with this virus. The number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide with about 675,000 occurring in the United States.The 100-year anniversary of the 1918 pandemic and the 10-year anniversary of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic are milestones that provide an opportunity to reflect on the groundbreaking work that led to the discovery, sequencing and reconstruction of the 1918 pandemic flu virus. This collaborative effort advanced understanding of the deadliest flu pandemic in modern history and has helped the global public health community prepare for contemporary pandemics, such as 2009 H1N1, as well as future pandemic threats.

The 1918 H1N1 flu pandemic, sometimes referred to as the “Spanish flu,” killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide, including an estimated 675,000 people in the United States. An unusual characteristic of this virus was the high death rate it caused among healthy adults 15 to 34 years of age. The pandemic lowered the average life expectancy in the United States by more than 12 years. A comparable death rate has not been observed during any of the known flu seasons or pandemics that have occurred either prior to or following the 1918 pandemic.

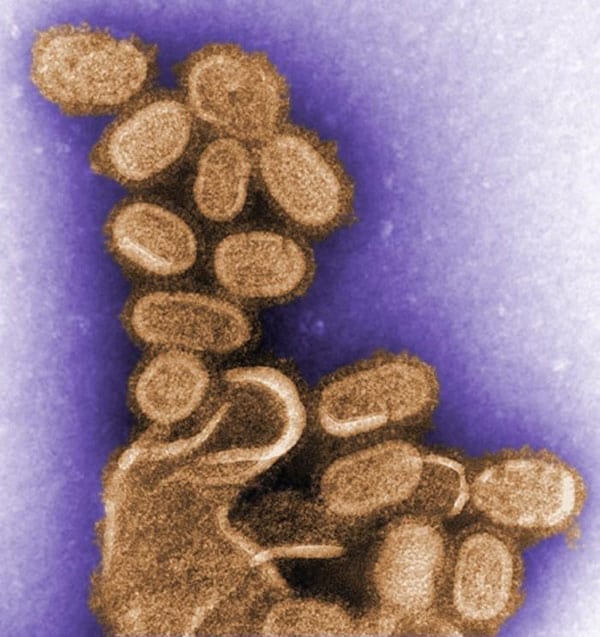

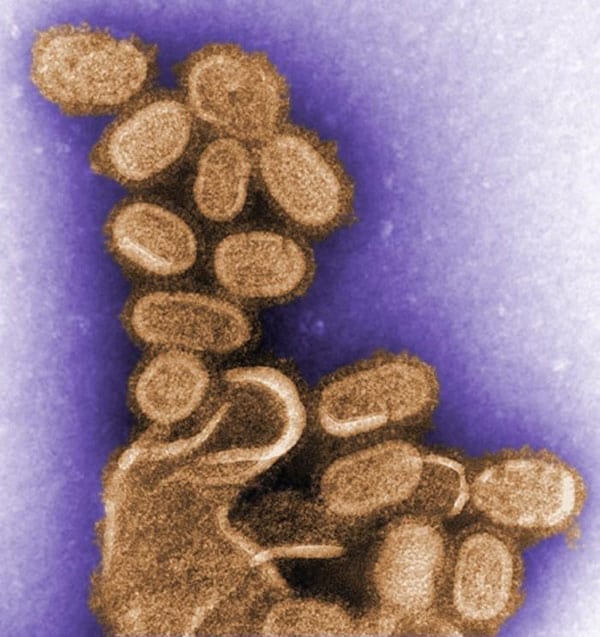

A colorized image of the 1918 virus taken by a transmission electron microscope (TEM). The 1918 virus caused the deadliest flu pandemic in recorded human history, claiming the lives of an estimated 50 million people worldwide.

For decades, the 1918 virus was lost to history, a relic of a time when the understanding of infectious pathogens and the tools to study them were still in their infancy. Following the 1918 pandemic, generations of scientists and public health experts were left with only the epidemiological evidence of the 1918 pandemic virus’ lethality and the deleterious impact it had on global populations. A small ocean-side village in Alaska called Brevig Mission would become both testament to this deadly legacy as well as crucial to the 1918 virus’ eventual discovery.

Today, fewer than 400 people live in Brevig Mission, but in the fall of 1918, around 80 adults lived there, mostly Inuit Natives. While different narratives exist as to how the 1918 virus came to reach the small village – whether by traders from a nearby city who traveled via dog-pulled sleds or even by a local mail delivery person – its impact on the village’s population is well documented. During the five-day period from November 15-20, 1918, the 1918 pandemic claimed the lives of 72 of the villages’ 80 adult inhabitants.

Most influenza outbreaks disproportionately kill the very young and the very old, with a higher survival rate for those in between, but the Spanish flu pandemic resulted in a higher than expected mortality rate for young adults. Scientists offer several possible explanations for the high mortality rate of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Some analyses have shown the virus to be particularly deadly because it triggers a cytokine storm, which ravages the stronger immune system of young adults. In contrast, a 2007 analysis of medical journals from the period of the pandemic found that the viral infection was no more aggressive than previous influenza strains. Instead, malnourishment, overcrowded medical camps and hospitals, and poor hygiene promoted bacterial superinfection. This superinfection killed most of the victims, typically after a somewhat prolonged death bed.

The Spanish flu was the first of two pandemics caused by the H1N1 influenza virus; the second was the swine flu in 2009.

When an infected person sneezes or coughs, more than half a million virus particles can spread to those nearby. The close quarters and massive troop movements of World War I hastened the pandemic, and probably both increased transmission and augmented mutation. The war may also have increased the lethality of the virus. Some speculate the soldiers' immune systems were weakened by malnourishment, as well as the stresses of combat and chemical attacks, increasing their susceptibility.

A large factor in the worldwide occurrence of this flu was increased travel. Modern transportation systems made it easier for soldiers, sailors, and civilian travelers to spread the disease.

In the United States, the disease was first observed in Haskell County, Kansas, in January 1918, prompting local doctor Loring Miner to warn the US Public Health Service's academic journal. On 4 March 1918, company cook Albert Gitchell, from Haskell County, reported sick at Fort Riley, a US military facility that at the time was training American troops during World War I, making him the first recorded victim of the flu. Within days, 522 men at the camp had reported sick. By 11 March 1918, the virus had reached Queens, New York. Failure to take preventive measures in March/April was later criticised.

In August 1918, a more virulent strain appeared simultaneously in Brest, France; in Freetown, Sierra Leone; and in the U.S. in Boston, Massachusetts. The Spanish flu also spread through Ireland, carried there by returning Irish soldiers.[citation needed] The Allies of World War I came to call it the Spanish flu, primarily because the pandemic received greater press attention after it moved from France to Spain in November 1918. Spain was not involved in the war and had not imposed wartime censorship.

Comments

Post a Comment